What Retail Can Teach Us About Saving the World

How Category Management Can Reset Global Governance

TL;DR: Can Category Management Fix Global Governance?

The world’s institutions (UN, IMF, WHO, NATO) resemble a cluttered, outdated store shelf.

Redundancy, overlap, and poor role clarity plague global coordination.

This essay applies retail category thinking (planograms, SKU roles, attach logic) to reimagine a system that delivers results, not just signals.

What if the world needs a category reset, not a revolution?

I. Intro — The Planet as a Planogram

“If Earth were a store, would anyone know what aisle to walk down?”Walk into a poorly merchandised store, and you know it instantly.

Too many signs. Core items buried. You leave frustrated, wondering if anyone’s in charge.

Now imagine Earth, but not as a metaphor, but as a system. Because systems, when mismanaged, behave in predictable ways…whether you’re selling soap or solving climate change.

This isn’t about trivializing global institutions; it’s about making them legible. As I’ve leaned deeper into category management, whether it’s designing assortments, clarifying roles, resolving overlaps, I started to notice a pattern: the dysfunction we see in our international institutions feels eerily familiar.

Global bodies such as the UN, IMF, WHO, WTO and NATO were established to oversee the essential categories of civilization: peace, trade, health, migration, climate and technology. They were meant to coordinate, stabilize and guide. But instead of coherence, we see chaos, overlap, gaps, redundancy, and turf wars. Structures stretched across challenges they weren’t built for. Messaging without fulfillment. Presence without precision.

These aren’t random breakdowns. They’re symptoms of bad architecture.

And if you’ve ever had to fix a broken category, you know the signs:

Too many lead SKUs and no attach logic.

Overloaded master brands with no inventory control.

White space left to third parties or unaccountable players.

So I’ve started to ask: What if global governance isn’t broken? What if it’s mis‑merchandised?

What if the world needs a category reset, not a revolution?

II. The UN — A Master Brand with No Inventory Control

If the United Nations were a product on the shelf, it would be the one everyone recognizes but few actually pick up.

You nod at the packaging. You respect the tagline: Peace. Cooperation. Global unity. But you’re not sure what’s inside. Or if it even works.

The United Nations wasn’t built to handle everything. It was built to prevent one thing from happening again: global war.

Formed in 1945, in the smoldering aftermath of World War II, the UN’s founding mission was to maintain international peace and security through cooperation, dialogue and collective action. (Sounds like category management, right?)

The world had just witnessed genocide, nuclear devastation and the collapse of the League of Nations. This time, the architects, led by the Allied victors, wanted something stronger, more durable, more structured.

The Security Council was created to manage threats to peace. The General Assembly ensures dialogue among nations. Specialized agencies like the WHO and UNESCO were added later, like limbs growing from a body still adapting to modernity.

And for a time, it worked. Or at least, it functioned.

The UN provided a stage for diplomacy, helped newly independent nations gain sovereignty and shaped the post‑war international order.

But here’s what’s often missed: even the best‑designed structures only work when cooperation exists.

That’s true in governance, and it’s true in category management.

You can build the most elegant planogram, assign the clearest roles, design the smartest modular layout. But if the players don’t align, if the SKUs compete instead of complement, if suppliers refuse to collaborate, the system breaks. Shoppers get confused. Sales suffer. The aisle underperforms.

Global governance, like a complex category, depends on cooperative execution, not just intention. It requires actors to show up, share data, follow through and adapt when conditions change.

That was the UN’s strength at its best…and it’s the risk today, because cooperation isn’t hard‑wired. It must be maintained, managed, renewed.

Without that, both governance systems and commercial ones drift into redundancy and irrelevance, no matter how noble the original blueprint.

But over time the world changed. The UN didn’t.

In category terms, the UN is now a master brand with bloated architecture and no inventory control. It stretches across too many lanes: peacekeeping, health coordination, refugee aid, climate frameworks, human rights, sustainable development.

Yet the UN lacks teeth. It lacks centralized authority, clear prioritization and operational accountability. It’s everywhere. And nowhere.

It brings awareness. It brings legitimacy. But it doesn’t convert the basket.

And in governance, closing the basket means real‑world impact…stopping a war, deploying aid, brokering deals, containing pandemics. Without the power to compel actors or coordinate execution across its own agencies, the UN becomes the ultimate top‑of‑funnel brand: signaling intention, generating headlines, rarely driving resolution.

We saw it in Syria: the Security Council deadlocked, humanitarian corridors collapsed, resolutions were passed then ignored. Over half a million people died while the UN stood visibly present, loud but largely powerless.

We saw it again during COVID‑19: the WHO issued early alerts, but member states disregarded them. Vaccine hoarding followed. Coordination collapsed. COVAX, while noble, was reactive and underfunded…an example of good branding without deep fulfillment capability.

We see it today in Gaza and Ukraine, where the UN is often the platform for statements, not solutions.

From a category‑management perspective, this is a classic failure of role clarity and attach logic. The UN should be the connective tissue of the global system, such as a master brand that unifies and elevates the work of its sub‑brands. Instead, it behaves like a loose federation of competing SKUs, each with its own mandate, budget and narrative: WHO, UNESCO, UNHCR, UNDP…often duplicating efforts, occasionally clashing, rarely bundling.

A category manager would ask the obvious questions:

What is this institution actually for?

Where should it lead, and where should it support?

Why aren’t its sub‑brands working together to create synergy?

In retail, you’d reassort. You’d rationalize the architecture. You’d pair the UN’s global awareness with executional partners that can deliver on what it signals. You’d define attach logic, bundle services and clarify outcomes.

Because a master brand without fulfillment isn’t leadership.

It’s just signage. And signage can’t solve a refugee crisis, broker a cease‑fire or contain a virus.

It just reminds us that someone should.

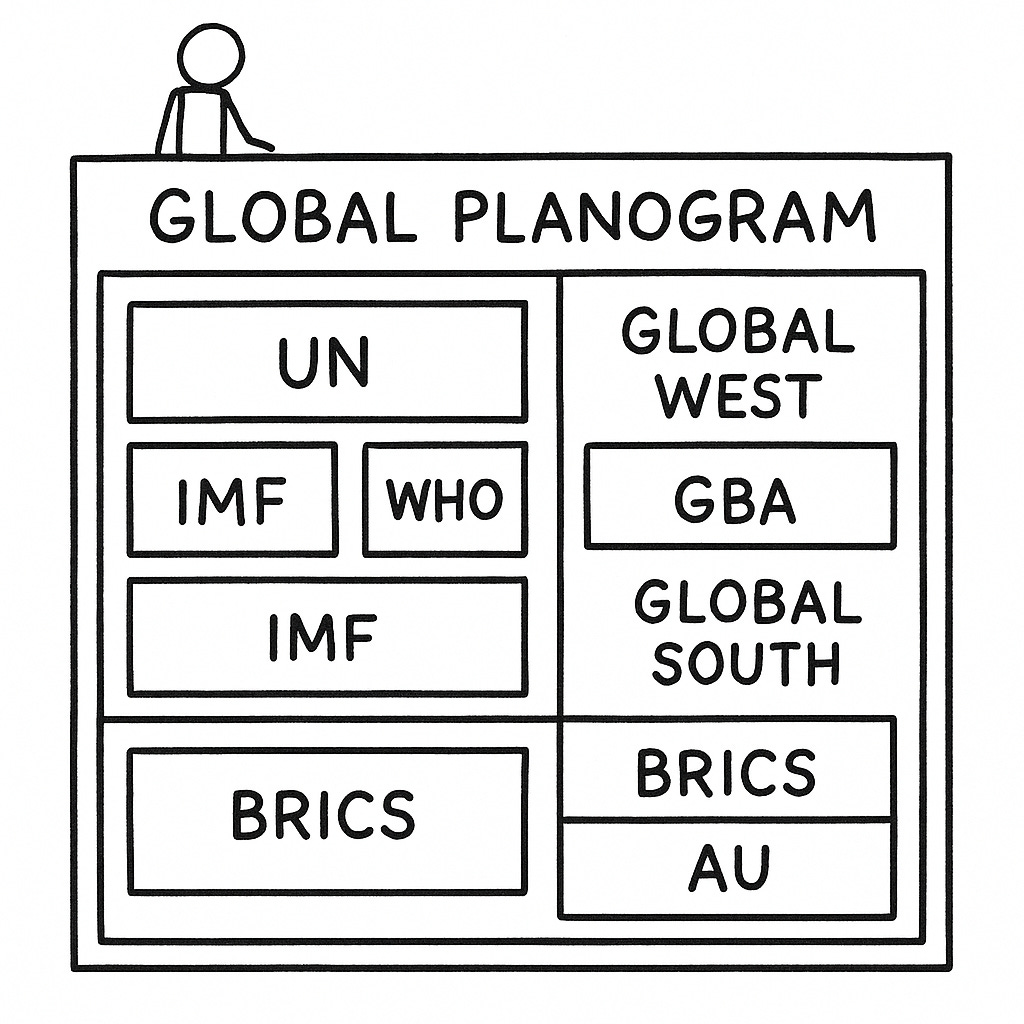

III. NATO, G7, IMF: Eye-Level SKUs for the Global West

If the UN is a master brand with broad reach and shallow execution, institutions like NATO, the G7 and the IMF represent the opposite: narrow focus, deep power and premium shelf placement, but only for a specific segment of the global shopper base.

These are the hero SKUs of global governance. They dominate eye‑level space. Their packaging signals credibility. Their placement tells the world: this matters.

Their roles are clear. NATO ensures security among Western allies. The G7 shapes economic policy among the wealthiest democracies. The IMF stabilizes currencies and lends in crises. These institutions are well‑funded, reinforced by infrastructure and protected by legacy networks of trust and influence.

But like any assortment built for yesterday’s shopper, they now face a segmentation problem.

They were designed to preserve post‑war power structures, not to serve a truly global audience. Their frameworks were optimized for a Cold‑War logic: binaries, blocs and borders. While the world diversified, they didn’t.

To much of the Global South, these institutions feel visible but distant, familiar, yet inaccessible. Present in language, absent in ownership.

They often set rules they don’t apply to themselves: champion fiscal discipline abroad while tolerating deficits at home; promote open markets yet preserve tariff walls; fund development but with conditionalities that limit autonomy.

The result? A system that signals global relevance while operating as a closed loop…guidance and governance tailored to the needs of its original architects, with limited adaptability to emerging players.

Consider that BRICS nations now represent a larger share of global GDP (PPP) than the G7, yet lack equivalent influence in key decision‑making bodies. India is the world’s most populous country. Brazil is Latin America’s largest economy. Yet neither holds a permanent seat on the Security Council or leads major financial institutions.

In retail terms, we’ve kept the same brands at eye level for 80 years, not because they’re still the most relevant, but because the planogram hasn’t been updated.

A smart category manager wouldn’t erase these institutions; they still serve core missions. But they would ask:

Are these still the right lead SKUs for today’s global market?

Who else deserves prime placement based on contribution and capacity?

What new products are emerging that could serve unmet needs more effectively?

When shelf space never rotates, you’re not managing a category…you’re curating a museum.

And museums are important, but they don’t drive growth. They preserve history.

IV. The Cluttered Aisle: Chaos, Gaps, and One-Size-Fits-All

In retail, a well‑structured aisle feels effortless. Shoppers move with flow; products are sequenced with logic; roles are clear, leaders up front, essentials in the middle, adjacents nearby. When the structure breaks down? Confusion. Redundancy. Paralysis.

That’s where global governance is now: stuck in a cluttered aisle with no coherent planogram…overlapping roles, invisible gaps and a one‑size‑fits‑all mentality.

Take climate. The UNFCCC sets frameworks. The World Bank funds adaptation. The IMF folds climate into fiscal policy. National governments implement projects. NGOs fill cracks. Tech firms offer carbon dashboards and offset platforms. But no one owns the journey end‑to‑end. Who’s accountable when emissions rise? Who manages cross‑border execution? Who defines success?

Then there’s COVID‑19—not as theory, but lived failure. Despite decades of global health architecture, the pandemic exposed the system’s fault lines. Nations hoarded PPE. Supply chains collapsed. The WHO issued guidance but lacked power. The world scrambled to build a global logistics response during the crisis instead of having one in place. Coordination didn’t just fail. It had never been built.

Look at migration. More than 281 million people were international migrants in 2020, yet no global institution truly governs labor mobility. Talent pipelines are blocked. Humanitarian systems are overrun. Border policies contradict one another. The white space isn’t theoretical; it’s visible in detention camps, worker shortages and broken asylum systems.

Across issues, global policy assumes uniformity. Frameworks are drafted in Geneva and expected to work in Lagos, Jakarta or Caracas. But what fits Germany doesn’t fit Ghana. Digital‑inclusion strategies fail in countries with poor bandwidth. Climate goals falter when they ignore development baselines. Debt‑relief policies collapse when they rely on institutions people don’t trust.

This is the triple failure:

Overlap creates chaos. Too many actors in the same space, fighting for the lead.

Gaps create vulnerability. No one owns key outcomes, so nothing gets delivered.

Uniformity breeds inequity. Policy templates ignore the context they’re dropped into.

In commerce, we solve this with segmentation. We localize assortments, tier offerings, create modular pathways for different needs and different shoppers.

Global governance should do the same, but not as fragmentation, but as structured flexibility.

Because when every SKU tries to lead, nothing leads. When no one owns fulfillment, nothing ships. And when every shopper is treated the same, most walk away empty‑handed.

V. Planogram Power – Who Gets the Eye-Level Shelf?

Shelf placement isn’t decoration; it determines what gets seen and what gets ignored. Eye‑level spots drive trust and traffic. They quietly tell the shopper: this matters most.

In global governance, the same quiet force shapes the world.

Institutions like the G7, the UN Security Council’s five permanent members and major donor coalitions have long held those premium slots. They headline the summits. They draft the frameworks. They signal legitimacy before a single word is spoken.

But the planogram hasn’t been refreshed since 1945.

Consider this:

India’s 1.4 billion people fuel peacekeeping, technology and growth, yet the country has no permanent seat at the global power table.

Nigeria is projected to become the world’s third‑most‑populous country by 2050 and is a cultural and economic hub, yet it remains peripheral in climate, trade and digital‑policy forums.

Meanwhile, France and the UK, each under 70 million people, retain outsized voices due to historical wartime alliances.

Even definitions of “developed,” “stable” or “trustworthy” often come pre‑loaded with Western bias, reinforced through control of ESG standards, digital‑governance norms and development‑loan terms.

This isn’t a naive argument for equal shelf space for everyone. Some governments are unstable. Some regions are in crisis. Some actors, such as autocratic regimes, rogue states, military juntas, do not deserve greater prominence. The goal isn’t automatic inclusion.

The goal is intentional rebalancing:

Placement based on present‑day contribution, regional leadership and constructive engagement…not historical privilege alone.

Visibility earned through transparent governance, global cooperation and real institutional capacity…not just GDP or population.

A modular system that allows for rotation, probation and accountability, so shelf space is a function of performance, not permanence.

Legacy reinforces placement; placement reinforces legacy. Defaulting to legacy excludes emergence and cements stagnation.

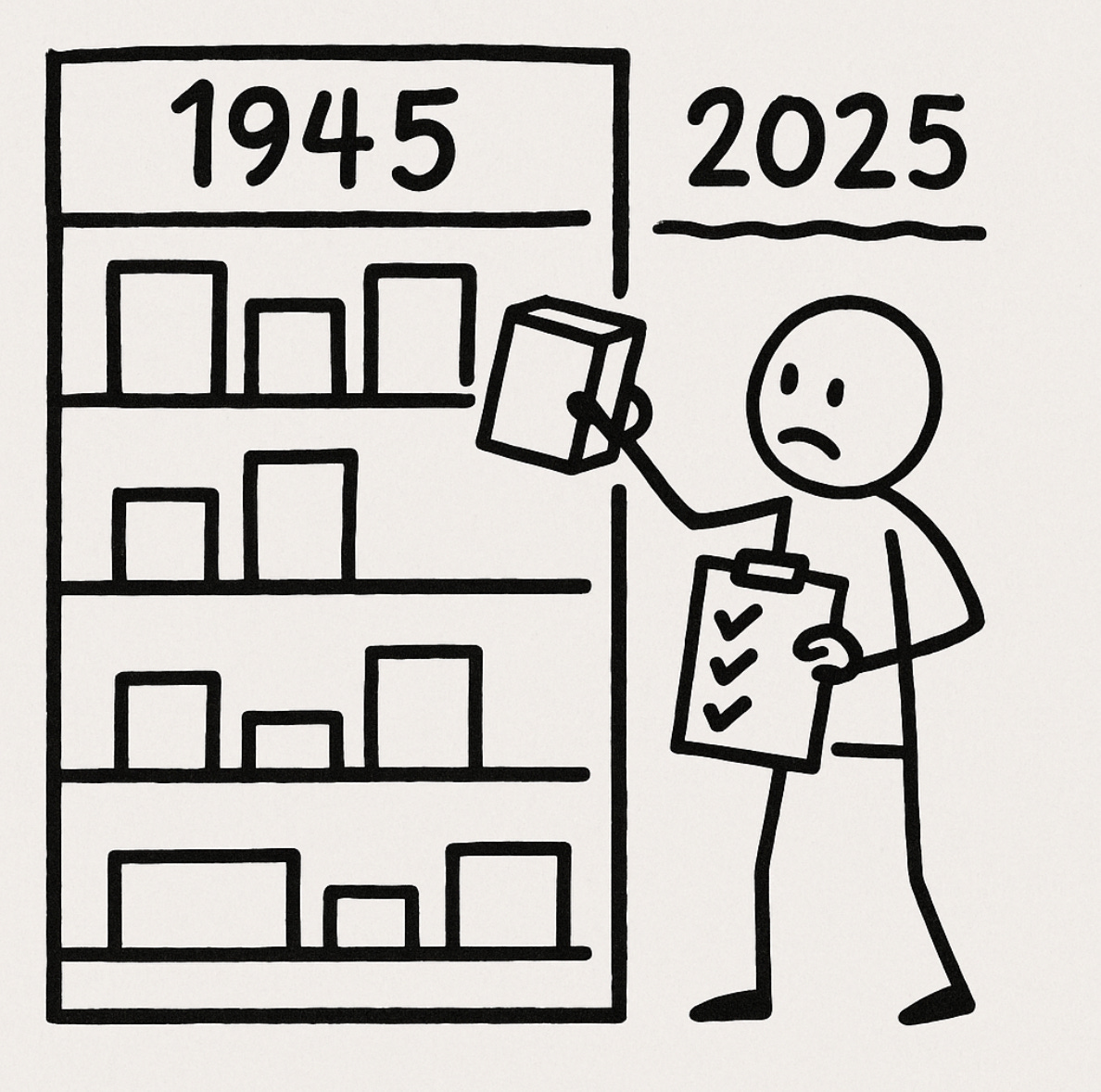

VI. The Global Category Reset – A Thought Experiment

There’s no global buyer or no chief merchant of humanity reviewing our institutional shelf and asking, “Is this still working?”

But imagine if there were.

A global category reset wouldn’t start from scratch; it would reorganize what we already have: Clarifying roles, eliminating redundancy, closing gaps and aligning structures to the reality of 2025, not the memory of 1945.

Because when category managers ignore the shelf, they don’t just risk inefficiency, they risk dissatisfaction. Shoppers get confused. Attach logic breaks. Core items go undiscovered. Eventually, traffic moves elsewhere.

Governance isn’t so different. Keep pushing coordination through outdated structures and we’ll see the same thing: fracture, distrust, paralysis.

Take climate. Responsibilities are scattered: the UN sets goals, the IMF integrates metrics, the World Bank funds resilience projects, NGOs fill gaps, private companies pledge targets. No central backbone for accountability. Deadlines slip, emissions rise, nations stop believing the process works.

Consider AI governance. Language models, surveillance tech and predictive tools are exploding across borders, yet we have no global framework for oversight. Companies write their own rules; governments scramble to catch up. Without an effective coordinating body (one with legitimacy and teeth), we risk a fragmented digital world where authoritarian regimes exploit loopholes, democracies fail to respond and trust erodes.

The pandemic gave us a preview. The WHO issued warnings, but coordination faltered. Nations hoarded vaccines. Supply chains broke. Trust in institutions cratered.

If the next crisis hits, whether it be biological, ecological or digital, and we’re still relying on the same disjointed playbook, the breakdown will be faster, deeper, harder to recover from.

That’s the consequence of ignoring the shelf…of pretending the modular still works because it once did.

So what would a reset look like?

Assign clear roles. Institutions specialize based on structural strengths, not historical mandates. Agencies that duplicate merge; those that conflict align transparently.

Fill the white space. Not with treaties, but with testable formats such as AI ethics boards, climate‑mobility coalitions, digital‑infrastructure accelerators. More alignment, less bureaucracy.

Tie funding and visibility to performance. Outcomes drive prominence; institutions that can’t adapt are retired, merged or downgraded.

Connect the systems. A refugee‑relief effort could activate UNHCR, WFP supply chains, IMF financial modeling and third‑party digital‑ID solutions, built into the same activation loop. Modular, scalable, interoperable.

Structure alone isn’t enough. Power, funding and leverage matter.

A modern system might be funded partly through micro‑taxes on global transactions on things like carbon, digital infrastructure, even AI usage, aligning contributions with externalities. Power would come from results: institutions that coordinate well and deliver measurable outcomes earn trust and prominence. Success attracts participation.

Leverage would come from new keys: data authority, digital infrastructure, trust ratings, platform access. Visibility becomes soft power; reputation becomes enforcement.

Right now, the shelf doesn’t reflect the shopper. Our systems don’t reflect citizens’ needs. People fall through the cracks.

A global category reset won’t guarantee peace or prosperity. But it would give us a structure that can respond to reality.

Without it, we’re not managing complexity. We’re drowning in it.

VII. Reflecting: If Humanity was a Category Portfolio

This isn’t about replacing values with spreadsheets. Systems this important deserve structure.

Category management isn’t about control; it’s about coherence.

What if we brought that same discipline to global governance…assigned roles, not just ideals; designed for complexity, not just consensus; matched structure to purpose?

Global governance isn’t broken. It’s mis‑merchandised.

And if we keep treating a 1945 shelf like it still fits a 2025 world, even the best portfolios will drift.

Drift, left unchecked, doesn’t just stall progress.

It erodes trust. And trust, once gone, is hard to restock.

—Quy

Enjoy this kind of systems thinking?

Subscribe to The Marketplace for essays on commerce, governance and the quiet architecture of modern life. No noise, no hype, just frameworks worth sitting with.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is the central idea of this essay?

A: That global governance isn’t necessarily broken…it’s misaligned, redundant, and outdated. Applying category management principles from retail offers a new way to structure global institutions.

Q: Why use retail metaphors like planograms and SKUs?

A: Because retail and governance both manage complexity through structure. Metaphors like “master brands,” “attach logic,” and “white space” make global dysfunction legible and actionable.

Q: What is a “global category reset”?

A: A reorganization of roles, responsibilities, and visibility within global institutions…like reassorting a messy store aisle to clarify leadership and drive fulfillment.

Q: Who should read this?

A: Policy thinkers, systems designers, retail professionals, and anyone interested in how structure shapes outcomes…from commerce to geopolitics.